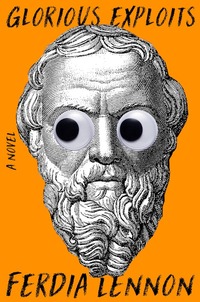

Glorious Exploits by Ferdia Lennon

Monday, March 25, 2024 at 9:24AM

Monday, March 25, 2024 at 9:24AM

Published by Henry Holt and Co. on March 26, 2024

I never tire of reading, but I do get tired of reading the same plots in book after book. Readers who think (in the words of Monty Python) it’s time “for something completely different” might want to check out Glorious Exploits. The novel is funny, surprising, and poignant.

The story is set in Syracuse early in 4th century BC. Syracuse at that point was populated by Greeks, but the prose is 21st century British (“Still a gobshite, I see.”).

Toward the end of the 5th century BC, Syracuse was invaded by Athens. With the help of Sparta, Syracuse defeated the Athenians. The story begins with captured Athenians imprisoned in a quarry, where they are visited by Lampo and Gelon, two unemployed potters. Like most Greeks in Syracuse, Lampo and Gelon are fans of Athenian theater. They are convinced that nobody does Euripides like the Athenians. On a visit to the quarry, Gelon gets it into his head to put on a production of Medea using the Athenians to act out the play. He finds a few who have acting experience and who know the parts. Lampo is taken with a green-eyed Athenian who he believes will be perfect for the part of Jason.

Lampo is even more taken with Lyra, a slave from Lydia (a kingdom that once existed on land that is now in Turkey). Lyra is owned by the proprietor of a tavern that Lampo often visits. Lampo falls in love with Lyra and promises to one day buy her freedom. That will be a difficult promise for an unemployed potter to keep, although it gives Lampo a resolve and purpose that he previously lacked.

Equal parts comedy and tragedy, the story follows Lampo as he works with Gelon to produce Medea. The captive Athenians are slowly starving to death, but the actors are incentivized by bread and wine. As Gelon and Lampo are casting the roles, they find an Athenian who not only knows Medea, but has acted in Euripides newest play, Trojan Women. Gelon believes that Athens is doomed and decides they must save the new play by bringing it to life. To that end, they plan to produce both plays.

Their plans come to the attention of a wealthy businessman named Tuireann who is passing through Syracuse. He provides the gold that Gelon and Lempo need to purchase sets and costumes to stage the play correctly. Yet not all Syracusans are pleased that the Athenians who killed their family members during a siege of the city are being treated so well. Will the plays ever be produced in the face of such hostility?

Glorious Exploits is in equal parts a comedy and a tragedy. Euripides (we are told at the end) “was ever in love with misfortune and believed the world a wounded thing that can only be healed by story.” Most of the story in Glorious Exploits unfolds between the invasion of Syracuse by Athens and its invasion by Carthage. During the years when Syracuse is free from invaders, Gelon and Lampo contrive to heal their wounded city with stories told by Euripides. Misfortune does indeed seem to be the human condition, particularly for slaves and captured soldiers who are starving to death in a pit. Some of them, at least, might be healed before the story ends.

The story told by Ferdia Lennon also has healing value. It is a story about the redemptive power of love and a story of the enduring power of Lampo’s rocky friendship with Gelon, but it is also the story of an unlikely friendship between Lampo and a conquered Athenian. The novel eventually becomes a story of how we should treat our enemies and whether we should think of other humans as enemies at all — at least in moments when we are not trying to kill each other.

Glorious Exploits has everything this reader could want: silliness, drama, excitement, unexpected twists, a story worth telling and lessons worth learning. The story is told in pitch-perfect prose that restores ancient Syracuse to its momentary glory. The year is young, but this is the best book I’ve read so far in 2024.

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

TChris |

TChris |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Ferdia Lennon,

Ferdia Lennon,  HR in

HR in  General Fiction

General Fiction