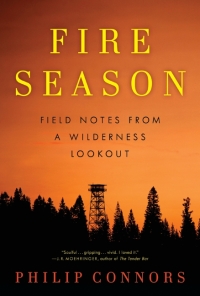

Fire Season by Philip Connors

Tuesday, April 19, 2011 at 12:29PM

Tuesday, April 19, 2011 at 12:29PM

Published by Ecco on April 5, 2011

Fire Season chronicles one of the many summers Philip Connors spent as a lookout in the Gila National Forest, sitting alone in a tower, scanning the treetops for smoke. Connors makes the arduous hike to his lookout post every year because "here, amid these mountains, I restore myself and lose myself, knit together my ego and then surrender it, detach myself from the mass of humanity so I may learn to love them again, all while coexisting with creatures whose kind have lived here for millennia." It is writing of that caliber, as much as the content, that makes Fire Season worth reading.

Although Connors writes lovingly of trees and grass, Fire Season is as much a tribute to solitude as it is an appreciation of nature's beauty. Connors writes that he does "not so much seek anything as allow the world to come to me, allow the days to unfold as they will, the dramas of weather and wild creatures." Connors channels (and makes frequent reference to) Abbey and Leopold in his descriptions of majestic nature, but also brings to mind (and sometimes quotes) Thoreau in his loving homage to isolation.

Connors peppers his book with lessons in history (the Warm Springs Apache hid from the Cavalry in the wilderness he now surveys) and biology (while moths, beetles, and tarantula hawks are some of the smaller creatures he observes, bears are a more frequent subject of comment). He provides a brief overview of conservationist philosophy and its history. Connors makes interesting what might in the hands of a less talented writer be dull, but the work still comes across as a hodge-podge: clusters of random facts connected only by their shared geography. Although the book is quite short, it reads as if Connors was searching for filler: a section discusses the unpublished notebook Jack Kerouc kept during his experience as a lookout; another discusses his experiences on 9/11; another recounts the vanishing wolf population in the Southwest. And given that the book it so short, it contains a surprising amount of redundancy: there are only so many times a writer needs to say that some fires are good and others not so good before the reader gets it.

My larger complaint (if it can be called that) about Fire Season is that it contains so little that is fresh. I'm not a biologist or ecologist or forester, but I knew before reading Fire Season (as I suspect most people did) that fires are necessary to the health of a forest environment, that the Forest Service didn't always understand that, and that public policy decisions about whether to let a fire burn are difficult to make and often controversial. Connors adds no depth to that discussion; his job is to look for smoke, not to make policy decisions, and his career is in journalism (and bartending), not forestry or firefighting. (There is, in fact, little in the book about the actual suppression of wildfires. Readers looking for an excellent fictional account of fighting forest fires should check out Andrew Piper's The Wildfire Season.) I'm not sure there's much to learn about fire from reading Connors' book that a reasonably well read person won't already know.

Connors' writing is strongest when it is most personal. Having a spouse who lives by himself in a tower every summer might challenge some marriages (while it might improve others); I thought it was interesting to read about the impact Connors' summer career has had on his marriage. When he writes about finding a fawn (apparently injured) and encountering hikers and the workings of his mind, Fire Season shines. Connors brings his dog into the wilderness for companionship and his description of the dog's personality change when transitioning to mountain life reinforces my belief that all books are made better by the inclusion of a dog.

In short, what Connors does in Fire Season has been done elsewhere, often in greater detail and with more authority, but the book nonetheless has value for the glimpse it provides of the sort of person who is content to sit in a tower for long stretches, pondering the wilderness, and for Connors' beautiful descriptions of (mostly) unspoiled forests and mountains.

RECOMMENDED

Reader Comments