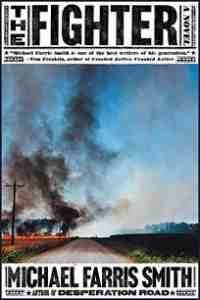

Lay Your Armor Down by Michael Farris Smith

Wednesday, May 28, 2025 at 6:53PM

Wednesday, May 28, 2025 at 6:53PM

Published by Little, Brown and Company on May 27, 2025

Lay Your Armor Down is a spooky story about three people who have survived hard lives and a little girl whose survival skills are even stronger. The story is as much about lives gone wrong as it is about a crime gone wrong.

The novel begins with an elderly woman lost to dementia who fills a shopping bag with cash she has been hiding and wanders into the woods, apparently guided by an inner sight. The woman’s name is Wanetah. The only person who ever checks on Wanetah is a woman named Cara. While Cara was the victim of abuse in an incident that taught her the risk of trusting people we don’t know well, she has not allowed her history to darken her heart.

Burdean and Keal make a living doing dirty deeds for anyone who will pay. They usually deliver duffels filled with contraband or rough up someone who owes a debt, but Burdean has been hired to retrieve something from the basement of a church. Burdean enlists Keal’s help. Burdean doesn’t know what they will find but he was told he’ll know it when he sees it.

The men delay the job when they notice a light in the church. They wait in the nearby woods to consider their options when Wanetah stumbles upon them. They relieve Wanetah of her cash before returning to their motel room.

Keal feels guilty about leaving Wanetah alone in the woods. He pictures her as prey for a wolf he saw. Keal returns without Burdean’s knowledge and, not knowing where to look for her, decides to check out the church again.

Outside the church, Keal finds a car riddled with bullet holes. He sees dead bodies inside and outside of the car. Venturing into the basement, he finds more dead bodies as well as Wanetah and a little girl. Keal finds Wanetah’s address on an envelope in her bag and takes her home, leaving her with his share of the cash he stole from her, before returning to the motel with the little girl.

The plot concerns the efforts of Keal, Burdean, and Cara to decide what to do about the little girl. She’ll only speak to Cara and doesn’t know why the bad guys want her, although Cara comes to understand that the bad guys (who may have watched too many X-Men movies) believe she has a superpower (or perhaps a supernatural power). Whether that’s true remains ambiguous throughout the novel. As is often true, evidence to support an unlikely theory may simply be a matter of coincidence.

Conflict arises between Burdean and Keal about whether they should sell the girl to the man who hired them. Burdean isn’t much of a thinker and few of his thoughts are dedicated to making moral choices. Burdean believes he is good at only three things — drinking, fighting, and fucking — and has little interest in expanding his horizons.

Keal, on the other hand, has spent his life being haunted by nightmares. He spent much of his life avoiding sleep, but the nightmares returned — dreams of storms and lightning — after meeting Cara and the girl. Whether his bad dreams are coming true is again ambiguous.

Cara is something like Keal in that, like Wanetah, she senses a reality that most people cannot perceive. Cara is also given to speeches that sound more like the product a literary crime fiction writer than the sort of prose a real person raised in unfortunate circumstances would employ — although, to be fair, eloquence is sometimes heard in unlikely voices.

Keal’s defining moment comes when he chooses his future, a choice that forces him to confront his role in the lives of Cara and the girl. “He closed his eyes and he could see the three of them hundreds of miles away in a stopsign town where little moved and little was questioned and he could sense a time when he would end up loving one or both of them and that was the last fucking thing he wanted.”

The story’s violent moments contribute to its unyielding tension as the plot advances. The quasi-supernatural elements didn’t work for me and too many questions (primarily about the dead bad guys and what the surviving bad guy intends to do with the child) are left unanswered, but the quality of Michael Farris Smith’s prose and his strong characterizations counterbalance an unconvincing plot. The ending is satisfying even if it fails to offer complete closure.

RECOMMENDED