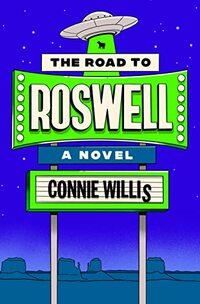

The Road to Roswell by Connie Willis

Wednesday, June 21, 2023 at 7:44AM

Wednesday, June 21, 2023 at 7:44AM

Published by Del Rey on June 27, 2023

Connie Willis’ time travel novels are some of the funniest — and remarkably insightful — works in the field of science fiction. In The Road to Roswell, she brings her sense of humor to a First Contact story, while goofing on people who attend UFO conventions with the absolute certainty that aliens walk among us, or are about to invade us, or at least make regular appearances to abduct us for a fun day of anal probing.

Francie Driscoll hasn’t taken much of an interest in UFO sightings. She’s invited to be the maid of honor for her former college roommate, Serena, who is getting married in Roswell during a UFO convention. A High Priest in the Church of Galactic Truth is presiding. The wedding was planned by Serena’s fiancé, a nutcase who takes UFO conspiracy theories way too seriously. This is not the first nutcase to whom Serena has been engaged. Francie believes it is her duty as a loyal friend to talk her down from her insanity.

As a Connie Willis fan might anticipate, Francie is abducted by an alien as she is retrieving wedding decorations from Serena’s car. She is thoroughly pissed off to learn that alien abductions are a real thing, upending her commitment to rational thought.

The alien resembles a tumbleweed but has remarkably strong and stretchy tentacles. She tries to report the abduction to the local police but they’ve had their fill of alien abductions. She manages to leave a message with an FBI agent who was invited to the wedding before the alien hurls her phone into the desert. She eventually names the alien Indy, after Indiana Jones (the tentacles remind her of whips).

Indy has Francie drive in multiple, seemingly random directions. A hitchhiker named Wade who stands in the middle of the road to make her stop is also abducted. Wade tells Francie that he’s a con man who on his way to Roswell to sell alien abduction insurance policies.

Indy decides they need a bigger vehicle so he abducts the driver of an RV (he calls the RV his Chuck Wagon). They add an elderly woman who is gambling at a casino and a UFO enthusiast named Lyle who believes every conceivable conspiracy theory about aliens, most of which he has drawn from science fiction movies.

Over time, all the abductees but Lyle become more curious than frightened, as Indy doesn’t seem to intend them any harm. They eventually become protective of Indy. Lyle, on the other hand, is convinced that Indy is the vanguard of an invasion force and is taking them to be anally probed.

Indy seems to understand Francie but can’t communicate with her until he learns to match written with spoken language. His English lessons consist of (1) pointing at road signs until someone reads them aloud and (2) watching westerns with the closed caption activated. The Chuck Wagon owner has pretty much every western worth watching. Indy comes to understand certain human concepts, including duty and friendship and loyalty, by watching westerns. On the other hand, he freaks out whenever Monument Valley appears, as it often does in westerns (regardless of where they are set).

The plot follows Francie as she attempts to understand Indy’s purpose for abducting her. He wants to go somewhere, but where and why are a mystery, as is his fear of Monument Valley. Indy is a decent little alien, if a bit annoying and demanding in the way a 5-year-old tends to be. The RV owner and the gambler have interesting personalities, while Lyle is the dolt you would expect a conspiracy theorist to be. Wade behaves mysteriously for much of the novel until Willis reveals his secret.

The story is cute. All its mysteries are neatly resolved in the last act. Willis doesn’t deliver the kind of rolling-on-the-floor laugher that she elicits with her best novels, but the plot and characters are consistently amusing. Willis adds a bit of romance with an ultimate “meet cute” that might be just a little too sappy, but romcom fans will be pleased. I wouldn’t be surprised if Netflix amps up the romance and turns The Road to Roswell into the movie. For the rest of us, the novel’s mockery of Las Vegas and UFO conspiracies, along with its reverence for classic westerns, is enough to make the novel worthwhile.

RECOMMENDED