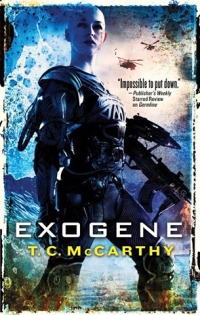

Published by Orbit on March 1, 2012

Germline, the first novel of The Subterrene War series, told the story of a journalist who became a part of the war he was covering, participating in battles and growing emotionally attached to genetically bred female soldiers called Germlines. In Exogene, the second novel in the series, the focus is on one of the Germlines, a genetic named Catherine. “Faith and death” is the genetic creed. Combat is a test of faith; death is the welcome reward, the entrance to a promised afterlife. Yet the reality of war changes people, even people who have been nurtured in vats and programmed to kill.

Catherine is a perfect killer. At 16 1/2, she is the finest genetic soldier ever produced in America. Yet Catherine begins to feel an unnatural (for a genetic) will to survive, a fear of death that may or may not be an early onset of the “spoiling” that awaits her at the end of her service. We know from the first novel that Germlines begin to rot away when they turn eighteen. We also know that despite being conditioned to accept that fate (while craving a more meaningful death on the battlefield), genetics occasionally try to run, to escape the war before reaching their expiration date, an effort that will prove to be futile -- or so they are told by their human creators.

Catherine’s story initially centers on her attempt to escape her makers and her engineered fate. She eventually falls into the hands of male genetics bred as Russian soldiers. The Russians are working on something new -- an Exogenic Enhancement, a hybrid of human and machine -- and who knows what the Chinese are doing (not to mention the Koreans). Hating Americans and Russians about equally, Catherine must make a choice about her future, and it is that choice that drives the novel’s second half. Since Catherine is handicapped by hallucinations in the form of flashbacks as her mind begins to erode, the second half blends Catherine’s present with snatches of her gritty past. Yet as the story unfolds and as Catherine’s conception of her purpose evolves, we begin to suspect that Catherine’s moments of superficial clarity are unhinged from reality. Whether due to spoiling or the drugs she was given or religious rhapsody, Catherine sometimes seems a tad crazy. That, of course, makes her an interesting character.

While T.C. McCarthy writes combat scenes that are as vivid and exciting as nearly any I’ve encountered in military science fiction, he also writes with poignancy that is too often missing from the genre’s war stories. McCarthy imbues his characters with greater depth than is common in action-driven stories. His vision of the future is interesting and more credible than most military sf novels I’ve read.

McCarthy makes impressive use of religion as the force that motivates the Germlines. The belief that killing is the path to salvation is a common feature of religious zealotry, a point that has been made often enough in fiction, but McCarthy takes it a step beyond the ordinary: What happens when a zealot begins to suspect that she is not serving God but is killing to serve secular masters? Or, in terms of McCarthy’s story, what happens when a genetic begins to worry that she is not a perfect instrument of God, but a flawed creation of man? When a genetic who is conditioned to hope the war will never end begins to long for -- not exactly peace, but a chance to kill on her own terms, to destroy an enemy of her own choosing? There is something both intellectually and emotionally engaging about Catherine’s redefinition of her life’s purpose. Perhaps Exogene is about the true meaning of freedom (nothing left to lose?) but I think its meaning is open to other interpretations, particularly in light of an unexpected ending that made me question my understanding of Catherine. That’s one of the things I like about Exogene and Germline: the novels work as high energy action stories but they operate on other levels as well, giving the reader political and philosophical meat to chew upon.

I felt for the journalist in Germline more deeply than I connected with Catherine, but I think Exogene is in many ways a more cohesive work than its predecessor, and the better of the two novels, albeit only slightly. Both are worth reading, and I look forward to the next installment.

RECOMMENDED