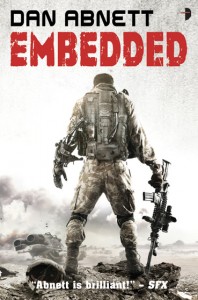

Published by Angry Robot on March 29, 2011

I don’t go out of my way to read military science fiction because it is so often unimaginative. John Scalzi is an admirable exception to that rule, an inventive storyteller who gives complete personalities to credible characters. Like Scalzi, Dan Abnett has a loyal following so I thought I would try one of his novels. Perhaps I picked the wrong one.

Lex Falk is a journalist who describes himself as an arrogant jerk (“jerk” being a euphemism because I’m writing this for a family audience). He’s on a world known by its number (86) covering an armed dispute. The planet is being developed for mineral extraction. The most productive settlements on 86 belong to the “United Status” (a little too cute, that) which wants to add 86 as a new state. The official story -- the one Falk is investigating -- is that “anti-corporate paramilitary forces are staging armed resistance” to US activities on 86. The truth is more complicated and appears to pit the US against the Bloc (whose soldiers speak Russian). The Settlement Office Military Directorate (sort of the United Nations of interplanetary land claims) has been charged with containing the dispute. Falk is embedded with the SOMD to gain a reporter’s view of the conflict, but the SOMD prevents him from seeing anything worthwhile. Fortunately for Falk (and for the plot), a public relations consultant employed by a corporate entity with a vested interest in the dispute decides Falk should know what’s really happening. At that point Falk is embedded by means of a virtual connection to a soldier (he sees what the soldier sees) and the action finally begins.

And quite a lot of action there is. Once it starts, the action is nonstop and some of the combat scenes create real tension. Although Abnett’s writing too often seems designed to titillate preteens, the plot has some entertainment value once he gets the story in gear. As a result of the embedding, Falk finds himself wrestling with a moral dilemma that is well conceived. Some of the story is quite funny, although I doubt that the humor is always intentional. A few of Abnett’s ideas about life on frontier worlds are innovative. The timeless conflict between the governmental desire for secrecy and the media’s desire to expose those secrets is an effective storyline that provides a reasonable excuse for all the descriptions of battle, although the mystery of the cause for all the fighting turns out to be anti-climactic.

Abnett relies heavily on dialog to carry the story but the dialog sounds a bit too 2011-hip to be credible. He tries hard to be gritty but it’s like listening to a one-note song. While I am a big fan of the F-word when it’s employed effectively, its frequent use in Embedded seems contrived, an easy way to demonstrate that the characters are rough and tough. When nearly every character drops an F-bomb in nearly every sentence, it becomes difficult to distinguish one character from another. (They make equally opportunistic use of nearly all the other words that can’t be uttered on network television; readers who frown on foul language will want to stay far away from this novel.) I did think the use of “freeking” as a “sponsored expletive” was clever; when characters who are likely to be televised use the F-word a “ling patch” converts the word to “freek” as they utter it, thus promoting a soft drink called NoCal Freek. If Embedded had demonstrated that level of originality more frequently, I would be more enthused about it.

In short, Embedded isn’t a bad effort, but it’s far from the finest example of military science fiction. I suspect that Abnett devotees and true military sf junkies will appreciate this novel more than I did, but I would hesitate to recommend it to the average sf fan.

RECOMMENDED WITH RESERVATIONS