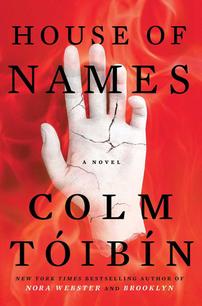

Published by Scribner on May 9, 2017

House of Names is a retelling of a Greek myth surrounding Agamemnon, Iphigenia, Elektra, Clytemnestra, Orestes, and Cassandra. You can’t beat Greek mythology for good stories that teach powerful lessons. That’s why the myths endure. Colm Tóibín adds characterization and detail to this powerful story of the ultimate dysfunctional family as a father plots against a daughter, a wife against her husband, and children against their mother.

The first section is narrated by Clytemnestra, the wife of Agamemnon, who desires revenge because he sacrificed their daughter Iphigenia to placate the goddess Artemis. Tóibín portrays Clytemnestra as a woman who understands politics (she is, after all, the wife of a king), a strong woman in a male-dominated world who manipulates people and power to attain her vengeful ends.

The next section follows her son Orestes after he has been taken by the soldiers who formerly served Agamemnon. Years and a number of adventures later, Orestes is on his way home, and the focus shifts to Elektra, who has clearly learned the art of manipulation from the mother she despises. Later the perspective shifts among the three key characters.

The story addresses a number of themes, including pretense (refuse to acknowledge your crimes, and it’s like you didn’t commit them); female subjugation and empowerment; the madness that comes with power and from being abused by power; the whispers and secrets that define a government; the impossibility of trust in a family that is built on betrayal; the cruelty of expectations; the consequences of revenge; how love blossoms from need; the burden of being a father’s son; and the evil that people do in the name of serving their god(s).

The gods, in fact, have had their day by the novel’s end. Leander, who becomes Orestes’ friend and later a conqueror of sorts, announces, in reference to the gods, that “we will get nothing more from them. Their time is over.” Shedding blood to satisfy deities is in the past, Leander thinks, but killing and maiming in the name of a deity is, sadly enough, still with us. I wonder if that might have been one of the points Tóibín intended the reader to think about.

Tóibín does justice to the myth in this embroidered retelling of a classic story. It is a new version of an old tale, and some details are clearly of Tóibín’s invention. Working from the strong foundation built by the likes of Euripides and Sophocles, Tóibín relates the story in graceful language that should appeal to a modern audience. By preserving a sense of detachment, he also avoids the melodrama that could so easily mar a story of such intensity. By any standard, House of Names is a compelling work of fiction by a masterful storyteller, backed by masterful storytellers from ancient times.

RECOMMENDED